Mary Hanna - Contributed

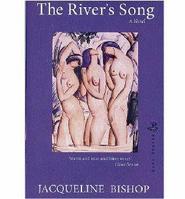

Title: The River's Song

Author: Jacqueline Bishop

Publishers: Leeds: Peepal

Tree Press, 2007. 181 pages.

Reviewed by: Mary Hanna

A coming-of-age story by Jamaica's Jacqueline Bishop, The River's Song has been warmly received by the region's woman cri-tics. Poet and storyteller Olive Senior has this enthusiastic response: 'I love The River's Song! It was so hard to put it down! Gloria's coming-of-age story is warm and true and bittersweet.' She goes on to say: 'The River's Song is a song we've all heard before, but never with such force and clarity as this.'

Senior is correct in pointing out the similarity of women's coming-of-age stories in the Anglophone Caribbean. Woman's writing speaks of school experiences, relationships with the mother, struggles with boys versus education and the ultimate choice to journey off-island to continue a mature path to higher learning. Books that clearly are highly autobiographical yet hold their own as creative narratives, these coming-of-age stories are welcome reading for young readers and older ones alike.

Merle Collins hails Bishop's 'moving and assured debut novel' precisely because it 'sings of the everyday struggles of Gloria and her mother in their Jamaican home'. She points out that the novel speaks of ambition and achievement, 'of the steady but troubled rise of a bright child who discovers that finding her own song could mean opposing those she most loves'. Gloria's journey is detailed and beautifully told, with a large cast of characters and locations. She is a child of the yard, and of the deep country where she spends summers with her beloved Grandy. She must make a heart-wrenching decision at the end of her school term: whether to stay on the island or to go abroad. Both options have the pain of disappointing friends and family that she must stand up to in order to put her choice into effect. Gloria ultimately finds the need for space to grow in a never-before-conceived environment to be the deciding factor and she opts for university in Minnesota. She has graduated with distinctions from a top Catholic school and bravely makes a hard decision that causes her best friend to become ill with disappointment: Gloria chooses to chart her own path, embark on her own journey. It has taken courage and faith. With this decision, Gloria has become a woman, no longer a girl.

Bishop's rendering of the childhood and school career of the lively girl Gloria is full of telling details and wound around with Caribbean fables and myths. She writes movingly of the rivermumma and weaves intricate stories into the text about plants and customs of deep rural Jamaica. Gloria has the great privilege of having access to the country in summers, and her group of friends there parallels the group she has in Kingston, in school and in the yard. The cast of characters, mostly women who have had to deal with disappointment in life owing to relationships with men, is large and riveting. The adults carefully watch the young girls and try to advise them, but the young women are often caught in poverty's relentless cycle and make mistaken choices thinking to better their lives. Nilda tries to get some ease from a life spent tending her mother's children by running away with an older man. Rachel, the yard prostitute, deeply regrets the young girl's choice and wishes she had had a chance to talk with her before she disappeared. Gloria, who is the last person to speak with Nilda before she leaves, keeps her own council - as she does on many occasions throughout her difficult journey to maturity. Gloria's powers of empathy and compassion prepare her for a life of containing secrets, a tool that comes in handy for her ultimate decision not to be a doctor but a wordsmith: she chooses to be a writer.

Bishop tells a well-controlled tale that is full of insight and sociologi-cally correct truths. She depicts life in the Kingston yard with realistic images and contrasts it to life in the great white house in the hills where Gloria's mother takes her family to live once she has married Zekie, a man who has made his fortune in America and returned home. Always mysterious about the source of his wealth, Zekie has a hard time winning Gloria's trust, but ultimately she blesses the marriage of her mother and accepts Zekie's generosity with gratitude. There is, however, a sense that things are not solid and may be prone to collapse at some point in the future. Gloria's relationship with her mother does not survive unscathed.

The flow of the narrative is strong and clear as the river that runs through the story. Always calling with its song, the river is a symbol of the lives of the young girls and their relationship to the older women who tend them and, sometimes, abuse them. Speaking of the yard, Gloria's mother says to Zekie: 'This is not a place to live and to bring up your children. Look what happen to Nilda. And she was a real nice child, that Nilda. And Denise, feisty though she was, look what happen to her. I know Gloria would never do anything so stupid, but I still want to get her out of this yard.'

She finds, however, that life in the hills among the middle class is desperately lonely. Gloria maintains her links with people in the yard, like Rachel, the good friend, and she wonders at the diversity of life in the island.

The River's Song is a flowing narrative of a Jamaican girl-child's arrival at maturity. It presents problems that Gloria must solve, and temptations - like Raphael, the handsome schoolboy - that she must resist. It is an engaging novel that, in the words of Merle Collins, makes you 'keep leaning closer to the novel to hear every word as it is being sung.'

Jacqueline Bishop was born and raised in Kingston, Jamaica. She is the founding editor of Calabash: a journal of Caribbean Arts and Letters and the editor of My Mother Who Is Me: Lifestories from Jamaican Women in New York. She has published widely in prestigious journals and presently teaches writing at New York University. She lives in New York City.