Arnold Bertram, Contributor

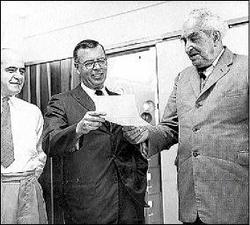

1962: The Hon. Sir Alexander Bustamante (right), Premier of Jamaica, receives from Mr. H.C. Minor, manager of the Jamaican branch of Texaco Caribbean Incorporated, a cheque for £5,000 towards Jamaica's Independence celebrations. The gift was made at the Premier's office. At left is Mr. Vincent McFarlane, permanent secretary to the Premier.

The PNP began its second term in office in 1959, having won 29 out of the 49 seats and a record 54.8 per cent of the popular vote. It was the first time since 1944 that the electorate had shown such confidence in an administration.

Despite its record in terms of economic transformation between 1955 and 1959, the administration was now faced with its share of challenges.

Party founder Norman Manley was now without two of his most important collaborators - Hugh Foot, whose term as Governor came to an end in 1957, and more importantly, Noel Nethersole, who died in 1959.

As future events would show, Vernon Arnett having been elected to the House of Representatives, demitted the position of general secretary, leaving an irreplaceable void in the organisation of the party.

Manley was left virtually alone to contend with the potentially explosive issue of the West Indies Federation, which was hardly going well. The Constitutional conference, held in September 1959 for the West Indian territories to discuss and settle outstanding issues for the Federation, ended in acrimony.

Each leader came away expressing resentment against somebody or something.

As a result, in reporting on the conference tothe House of Representatives on November 3, Manley had to urge his colleagues to support the view that Jamaica should remain in the Federation and do everything possible to make it work. Manley's insistence was based on his perception that the Federation was an essential pre-condition for Jamaica's independence. Th to a Federation of the British West Indies was in his view, permanent colonial status for Jamaica.

Jamaica Labour Party leader Alexander, Bustamante on the other hand returned to the view that political independence for Jamaica was not viable, neither on its own, nor in a Federation with the other West Indian territories.

As far as he was concerned, the perpetuation of colonial rule was a far better prospect for Jamaica than to be yoked with 'the pauperised territories of the Eastern Caribbean'.

Accordingly, his position in the debate was that Jamaica should leave the Federation immediately. His young JLP colleague, D.C. Tavares, proposed a referendum.

The Resurgence of Black Nationalism

However, the PNP prepared to deal with these challenges and to improve its record of economic and social development.

About this time, a group of Black Nationalists and Rastafarians shared the sentiments to unite and set up a righteous Government under the slogan of repatriation and power.

They began meeting regularly and called themselves The African Reform Church and their leader, the Rev. Claudius Henry, took for himself the title Repairer of the Breach.

This church established contact with the 'First African Corps' an armed militant black group in the United States with its headquarters in the Bronx, whose membership included Reynold Henry, son of the Rev. Claudius Henry. In early April 1960, the advance group of the First Africa Corp arrived in Jamaica and joined the militants from the African Reform Church in a guerrilla training camp in Red Hills.

Millard Johnson and the People's Political Party

Even as one group of black nationalists was preparing for guerrilla warfare, another group began to prepare for a constitutional political solution. In April 1960, barrister at law Millard Johnson launched the People's Political Party, a name borrowed from Garvey's organisation of 1928. Johnson was a founding member of the Richard Hart's Marxist Peoples Freedom Movement in 1954.\

The Division within the JLP

Before turning their energies to the PNP and Federation, the JLP had their fair share of internal problems to deal with. After losing the 1959 elections, the 75-year old Bustamante had taken an extended overseas holiday. Both Robert Lightbourne and D.C. Tavares now saw an opportunity to take over the party from the aging Bustamante and began their preparations.

The internal power struggle, which ensued, saw Rose Leon, the party chairman, supporting Tavares' bid. Matters came to a head at the JLP's annual conference in November 1960, which in Bustamante's absence elected Tavares over Lightbourne as third deputy leader. Instead of attending the second day of the conference, Bustamante sent a letter accusing one member of the top executive and a small clique of engineering forces at the Saturday session to control and manipulate the party to suit their own ends.

Bustamante then convened a new conference in January 1961, and secured an executive slate more to his liking. Gone was Rose Leon, who after losing the contest for 2nd deputy leader, unsuccessfully challenged the honesty of the ballot, and then resigned in tears, denouncing Bustamante as a liar. In 1961 she regrouped her followers in a Christian Democratic Party, which soon became the Progressive Labour Movement, before finally casting her lot with the PNP.

The Referendum on the Federation

Sir Alexander Bustamante addresses the House of Representatives in 1962. Until self-government, every ruling class resisted changes which would benefit the masses. - File photos

Norman Manley unilaterally committed the PNP to holding a referendum to decide whether Jamaica would remain in the Federation. The decision, while promoting democracy at the national level, violated the norms of internal consultation which characterised the PNP.

The lack of consultation with his senior party colleagues on this important decision was also a grave political error since there was a powerful group within the PNP led by the 1st vice-president of the party, Wills O. Isaacs, which harboured grave doubts about the viability of a West Indies Federation.

The JLP Takes the Initiative

Bustamante and the JLP now accelerated their anti-Federation campaign, hammering home to the Jamaican people that the wide spread poverty in Jamaica would only get worse with the additional taxation.

As the campaign progressed, Edward Seaga emerged as a major political personality, confirming the inability of the Jamaican poor to subsidise their neighbours in the Eastern Caribbean with his celebrated 'haves and have nots' speech, in which he alleged that as much as 93 per cent of the population constituted the 'have nots''.

Once the British announced that "with or without Federation, Jamaica would be given its Independence before the end of 1962", Bustamante became even more strident in his opposition to Federation. For him, not only was unilateral Independence the lesser evil for Jamaica, it was by far the most attractive political platform for the JLP.

The final inter-governmental conference held in Trinidad in May 1961, was followed by discussions in London organised by the Secretary of State for the Colonies to confirm the local decisions and adopt a final Federal Constitution. Manley and his delegation returned from the Lancaster House conference on the 17th of June to launch the PNP's Referendum campaign, confident of his party's capacity to repeat the victory of July 1959 and finish with Bustamante once and for all.

The Decisive Encounter

Once again, Manley underestimated Bustamante's genius in the art of political manipulation. At the sitting of the House, Norman Manley made a motion seeking acceptance of the Lancaster House White Paper, which would have moved Jamaica closer to a West Indies Federation. L.G. Newland, JLP member then moved an amendment to the motion introduced by Manley "rejecting the London report and requesting Her Majesty's Government to take the necessary steps to introduce legislation to grant Jamaica Independence on the 23rd May 1962 and to seek admission for Jamaica in the British Commonwealth as a Dominion".

This masterstroke of political opportunism by the JLP placed Manley and the PNP in the invidious position of voting against the first motion specifically seeking a date for Jamaica's independence. By the time of the election campaign, to the chagrin of the PNP Bustamante was being projected as the 'Father' of independence.

Having defeated the Opposition amendment, Manley was now forced to set a date for the referendum, which took place on September 19, 1961. Voters in the capital city supported the Federation, while rural Jamaica voted overwhelmingly against it. After the referendum, Bustamante made it clear that no discussions on independence could proceed without the participation of the JLP. In the third week of October 1961, a joint committee of the House was appointed to prepare proposals for Jamaica's Independence Constitution, which would then be taken to London for discussions and finalisation.

Among the owners of capital, there was serious concern that the man who replaced Nethersole as Minister of Finance was Vernon Arnett, the PNP's general secretary, who for two decades had earned the reputation of a man with impeccable socialist credentials. There was no doubt about the concern of the capitalist class about a Minister of Finance in independent Jamaica who had openly advocated nationalisation, operating with Cuba 90 miles away and the USSR in an expansionist mode. Their concerns were well articulated by Leslie Ashenheim a member of the Constitution Committee.

The Resurrection of Bustamante

With the announcement of general election to be held on April 10, 1962, both parties mounted their respective campaigns. In the third week of March, the JLP released its manifesto, which was obviously designed to target the farming community in particular and rural voters in general. The PNP followed with its 'Plan for a bigger, better, independent Jamaica', and a slogan with a picture of Manley captioned "Vote for the Man with the Plan".

Up to 1960, emigration particularly to the U.K., where a total of 58,946 Jamaicans had migrated between 1955 and 1958, had been the major factor in keeping unemployment down. However, with 8 per cent of all coloured migrants to Britain unemployed in 1958, coupled with the Notting Hill riots of that year in which some Jamaicans were brutally attacked by English youths, migration to Britain declined, and as a result unemployment climbed to 12 per cent by 1960.

By 1962, the deep divisions in the party over Federation, rising unemployment, and racial tensions had contributed to an increasingly disillusioned electorate. Simultaneously, the impact of international events as well as the rise of Black Nationalism had shaped a new consciousness in the psyche of the Jamaican people, which an aging and fractious PNP leadership seemed incapable of understanding. On the other hand, the JLP seemed energised. Its list of candidates combined an experienced old guard with newcomers Seaga, Jones, Eldermire and Gyles joining Tavares and Lightbourne to bring to the campaign a level of energy and dynamism that was never matched by the aging PNP.

In the campaign, the PNP had presence and certainly showed purpose. Popular response to Millard Johnson's militant 'black nationalism' reflected the level of racial oppression that existed, crying out for articulation and redress. Ironically, it was Manley's impressive economic and social gains which raised hopes and increased the demand for redress at a broader level.

On election day, Tavares, who had emerged as the JLP's organising genius, ensured victory in his own constituency in time to move his troops to Western Kingston to support his protégé, Edward Seaga, in the decisive encounter against the PNP's Dudley Thompson.

Some 580,517 Jamaicans cast their votes in the general election of 1962, of which 50.04 per cent voted for the JLP, 48.59 per cent for the PNP 0.86 for the PPP and 0.51 per cent for the independents. The JLP won 26 seats to the PNP's 19, to earn the right to lead Jamaica into independence. For Alexander Bustamante at 78 years of age, it was a political resurrection, which no one would have contemplated after his defeat in 1959. It is one of the ironies of history that it was the conservative, pro-British Bustamante and not the premier nationalist, Manley, who became the first Prime Minister in independent Jamaica.

Arnold Bertram is a historian, author and former government minister.