Laura Tanna, Contributor

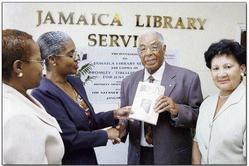

Bromley Armstrong hands over a copy of his autobiography 'Bromley: Tireless Champion for Just Causes', to Patricia Roberts, director general of the Jamaica Library Service, in 2006. The donation of more than 500 copies was facilitated by The Gleaner Company Ltd through its corporate affairs and marketing manager, Karin Cooper (left). Armstrong's wife, Marlene, shares in the occasion. - Ricardo Makyn/Staff Photographer

Bromley Armstrong experienced racial discrimination for the first time in his life in 1947 at a restaurant in the Miami Airport en route to Toronto. His brothers had served in the Canadian armed forces and tried for several years to gain Bromley's entry.

He remembers: "Most people don't realise that Canada, like Britain and Australia, had restricted immigration policies relating to the people of colour. In those days we were called 'Negroes' or 'coloured'. You couldn't get into those countries very easily. A white Jamaican could get into Canada with no problem. But a black Jamaican could not get into Canada. They told us we were British, brought up under the British Empire, British subjects, but under the Canadian Immigration Act, we were British objects, not subjects. This is my interpretation of the language!"

Bromley and younger brother George registered as students at the Toronto Business College, but no sooner had they arrived in the dead of winter than a fire from incorrect ventilation of the coal-burning furnace destroyed their possessions. Bromley sought work to no avail, often waiting hours in the cold to apply for a job.

1,600 black people in Toronto

"When I arrived, there were 1,600 black people in Toronto. We had one black lawyer, no doctor, no dentist. Not even a garbage collector. You just couldn't get jobs. Most of the black people got accommodation above Jewish stores," he recalls.

His brother Everald, an ex-Canadian soldier, prevailed on friends at Massey-Harris farm implements factory to find Bromley work.

Says Armstrong: "This big man came out, hollered ARMSTRONG, took me by the hand to personnel saying: 'If they ask you if you can operate a bulldozer, tell them yes.' So I visualise a bulldozer to be this big thing like a crane and I'm 147 pounds, my weight at boxing. I went in, filled out the application, had an interview and when the person said: 'When can you start?' I said: 'Yes, right away.'

"He took me all dressed up in my only suit, with tie, and introduced me to a little man, with muscular arms, named Beard from Barbados who was operating this bulldozer, a machine you put hot steel in, pull the lever, CRANK, and it bends it to what shape you want. Behind him is a firebox with flames shooting out, white flames the fire is so hot. He handed me gloves, and this tong four feet long."

Armstrong was to pick up steel with the tongs, place it into the firebox until white-hot, then move it to be shaped in the bulldozer.

"I couldn't even pick up the tongs and steel to put in the firebox. It was falling on the floor. The poor man is there just shaking his head. He turned to the foreman and gave him a look saying: 'You want to kill this young man?'

The young immigrant was taken instead to a Jamaican straw boss in the setting department where cool material not properly formed in the bulldozer is beaten into shape.

Employed persons

"He called a big fellow, Big John who was a Ukrainian, and said: 'Take this little fellow and look after him.' That's how I started at Massey Harris, 4,500 people employed, and I was there until 1956."

Armstrong still could not do the heavy work, but these Eastern European refugees did it for him because they needed a spokesperson: "I used to interpret English for them, to speak on their behalf to the foreman." So they asked him to be their union steward. He remembers: "At lunch time I used to place a board over the toolboxes and stand up and lecture them on life. If they wanted to better their circumstances they had to be cooperative and work together. All in my mind - this is January 1948 - there was Alexander Bustamante and Norman Washington Manley. Because as a kid in Jamaica I used to run around to meetings, any meetings, of politicians, churches, the Marcus Garvey Band marching down any street, I'd follow them because I wanted to hear the speaker. I was always inquisitive about these type of things.

Good relationship

"The Europeans just adopted me as a grandson, because these people were as old as my grandfather, maybe some (as old as) my father. They used to take me to their houses, give me pickles and wine they made, so I developed a good relationship with them and this is where I started off my whole career of caring for people and doing things for people, from these Europeans who needed people to talk for them.

"They were good workers. I was just a little, frail, skinny guy. Couldn't do anything. But what I lost in production, I made it in speaking on their behalf. I did everything for them. I would write grievances for them and I wrote a bulletin for the union and talk about the management, the foreman."

Armstrong vividly recollects: "I didn't know what discrimination was all about. Then you get into the workforce. When I saw what they were doing with the Europeans, how they called them DPs, despising them although they were WHITE. They were displaced persons (after World War II), that's what the Canadians called them. The Canadians hated them as much as they hated the blacks. And one of the things I saw, they hated Jews with a passion. So I got involved in the trade union movement, representing and speaking on behalf of people who couldn't speak for themselves.

Human rights and civil rights

"The United Auto Workers was the union in the factory and Walter Reuther, who was quite a trade union leader, insisted on people working on human rights. He wanted every local union to have a human rights committee. I got involved in human rights and civil rights and I've never looked back. I got so involved in unions that for years I was going to conventions in Montreal or Vancouver or some place and I was the only minority at any of these conventions. They were all white."

Armstrong notes: "I got so involved in the unions that I had to educate myself to compete with the Britishers that were the leaders. I took all kinds of courses in the union. Plus, I took a public speaking course and learned how to express myself and all the fine points of parliamentary procedures."

Armstrong highly recommends the famous Dale Carnegie course, 'How to Win Friends and Influence People', saying: "I went to the demonstration. When they called me up, I couldn't even tell them my name! But by the end of the 11-week course, I won every single award. It works. Believe me," he says.

The first thing Armstrong actually organised himself was the Caribbean Soccer Club in 1949 and got it into the Toronto District Soccer League and by 1951 he was a Canadian All-Star in that league. He then became involved in the Negro Citizenship Association and Credit Union becoming vice-president but after seven years left. "I was young and had too much vim and vitality for the older people because they believed in begging and I didn't. I believe in doing. They used to go to the city fathers, like the black ministers, always with their hand out, and they give you something, peanuts and to me I was just disgusted ... . I don't necessarily want a piece of the pie. I think we ought to make our OWN pie. You stop depending on people to do for you. You do for yourself!"

Racial discrimination

It was this attitude that gave Armstrong the stomach to personally fight racial discrimination, particularly in housing. Working in teams with white couples, he and a partner would apply at apartments or enter restaurants to test for discrimination. Through the Toronto and District Labour Council and the Ontario Federation of Labour, Bromley Armstrong and a Chinese student at the University of Toronto, Ruth Lor, won the first successful case in 1954 against two restaurants which discriminated against them.

Armstrong describes how he made history:

"In 1949 in Dresden, they had a referendum and voted 10 to one in FAVOUR of discrimination. That is why we took on that town. Lucky for us the premier at the time was Premier Frost, who enacted the first human rights legislation in Ontario, the Fair Employment Practices in '51 and in '54 Fair Accommodation Practices, which was the act we did the test cases under. He stood up in the House and said: "As long as I am premier of this province, there will be no second-class citizens. Everybody's going to be treated equally.' That's how my case went to court."

Meeting influential people

He acknowledges meeting many influential people in his life but notes:

"Two people impressed me: Premier Frost, because of human rights legislation which led the way for Ontario, and John Diefenbaker because he changed the immigration laws. We led a delegation to Ottawa in 1954, led by a man from Barbados, Donald Moore. I was the youngest member of that delegation. Nineteen of us went to Ottawa to ask them to change the immigration law because it was discriminatory. It never happened until 1962 when John Diefenbaker became prime minister of Canada and changed the immigration laws. That was a long wait from '54 to '62. So I'm very impressed with John Diefenbaker. I'm very impressed with Premier Frost. I keep those two people in my memory at all times."

Next: His return experiences in Jamaica and trials with white supremacists in Canada.