Gareth Manning, Staff Reporter

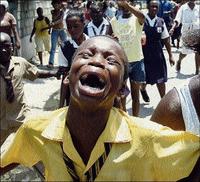

This little boy wails in anguish on hearing the news that a close relative of his was allegedly killed by the police. The increasing number of persons killed by cops under questionable circumstances has renewed calls for an independent body to be established to investigate extra judicial killings. - File

The year 2007 is quickly becoming the deadliest since 1983 for civilians who have died by the police gun, with 196 deaths so far into the year - a rate of 22 people each month. This is despite renewed training in the use of force over the past year to bring the number of cases of police excesses down.

Local human rights groups are once again rapping the lawmen for their undue use of force as Jamaica remains among the countries with the highest rate of police excesses, according to human rights lobby group Amnesty International.

The lobbyists are citing the bureaucracy of the system as being among the greatest challenges to the investigation of police killings. They point out that the process of sending files to the Director of Public Prosecutions is unnecessary and time consuming, due to heavy backlogs in that office. This backlog affords the accused cops time to flee the country, they quip, before a warrant can be issued.

Only 59 per cent of 3,207 cases since 1999 have been completed, data from the Bureau of Special Investigations show, with 167 cops arrested. One hundred and eleven have been acquitted while warrants are out for 19 cops.

"What is worrying is the pattern of impunity that is perceived," says Fernanda Doz Costa, researcher in the Americas Regional Programme for Amnesty International, who is on the island to conduct further research.

According to Doz Costa, there is public concern about the way investigations are treated because of the long period of time it takes for justice to be served. The method of investigation is marred by red tape and flawed techniques that often yield poor or no evidence, resulting in some cops being acquitted. And there has been no improvement since 2003, she says, when Amnesty, in a report to the United Nations, made special recommendations for the dispensation of justice on the island for cases of police excesses, as very little in those recommendations has been implemented.

Independent body needed

Among the changes lobbyists want is an independent investigative body to probe police misconduct, and a more rigorous system that should include psychometric and drug tests to ensure accused cops are clean before they are put back on the front line. They also want more measures to be put in place to hold police accountable for their actions.

Though Prime Minister Bruce Golding has announced that the Government will increase the powers of the police commissioner and set up an independent body with the purpose of cutting the red tape in investigative procedures and improving the service of justice, there is some scepticism as to how it will be implemented.

"The Prime Minister's investigative body is going to be critical because a large part of the problem that we have documented is real holes in investigating the police's use of force," comments executive director of Jamaicans for Justice, Dr. Carolyn Gomes. The organisation seems to be looking for more as it wants independence of the investigation to also include an independent forensic team inclusive of pathologists.

"It starts at the scene of the incident where policemen remove bodies, spent shells, etc., and critical and vital evidence is lost ... It then continues into the unacceptable post-mortem that is done by doctors employed to the Ministry of National Security and working very closely with the police, and ballistic samples are taken to the government forensic lab by the police," she says.

Executive director of Families Against State Terrorism, Yvonne McCalla-Sobers similarly, is of the view that there needs to be an independent forensic unit with more experts to quicken the production of forensic evidence and, hence, justice.

Nancy Anderson, human rights lawyer of the Independent Jamaica Council for Human Rights, shares a similar view. She is of the opinion that one such authority already exists in the form of the Police Public Complaints Authority, but the authority needs strengthening.

"We need an ombudsman who deals with complaints against the police. But, most importantly, it needs to have trained investigators who are not police officers," she says.

Power not exercised

Local human rights groups do not believe the powers of the police commissioner should be strengthened, without outlining the powers to which he will be accountable. They argue that this is necessary to ensure police are treated fairly. Moreover, the groups also argue, the commissioner has the power to hold cops accountable, but this is not being exercised often enough.

"There is a fair amount of power. The commissioner has the power to appoint, promote and dismiss below the rank of inspector. The question is, what is being done with the powers that are actually there?" Dr. Gomes queries.

"The disciplinary procedures outlined were outlined nearly 50 years ago and may be archaic and may need some revision. But there is a large question as to whether the power there is being exercised. [The answer is] no," she adds.