Gareth Manning, Sunday Gleaner Reporter

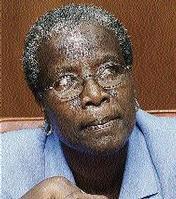

Mary Dixon, head of the Special Education Department at the Mico University College. - Andrew Smith/Photography Editor

A lack of specially trained teachers is creating a dilemma for institutions catering to children with learning disabilities.

According to Mary Dixon, head of the Mico College Special Education Department, there is a yearly exodus of trained teachers, leaving behind only about 10 per cent of graduates each year.

"Since the programme is regional the students coming to us from overseas have to go back to their countries and that could be half of the graduating class, and the others that are trained, because the government does not have a bonding system for them, go off to Cayman and the Bahamas or Turks and Caicos Islands, or they are recruited to go overseas," says Dixon. "So we are not seeing them staying when they are trained. They represent about another 40 per cent of graduates," she adds.

Principal of the Randolph Lopez School of Hope in St. Andrew, Christine Rodriguez says she has seen a significant drop in the number of trained staff in her institution. Trained teachers moved from about 50 per cent in the 1980s to under 30 per cent currently.

"So it means then that we have a serious problem; we are not turning out enough special education teachers," she says.

There are about 390 teachers currently working in special education institutions. Only 100 of them are trained in the field. They are not specially compensated either, says Hixwell Douglas of the Special Education Unit in the Ministry of Education, because teachers trained in special education are not necessarily considered specialists.

"I think primary school teachers will tell you they are specialists. Secondary school teachers will tell you they are specialists, so it all depends on the notion of specialisation," argues Douglas. "I am not so sure about the business of specialisation, it has certain kinds of implications, and from a personal point of view I think a lot of persons would want to consider themselves specialists, and that raises some very interesting questions," continues Douglas.

Some institutions try to fix the teacher shortage problem them-selves by training their own staff. Mrs. Rodriguez reports this is what is done at the School of Hope. The institution has ongoing workshops to make up for the shortfall in trained specialist teachers. The ministry also conducts training workshops for some teachers in the mainstream to help pad the lack of professionals.

In addition to inadequate teachers, there is also another staffing problem in these institutions. Most need clinical psychologists and there are not enough.

"When the child is identified, everybody recognises this child has a problem. It's not enough to say he has a problem. The teachers and the parents need help in how to deal with that child; so here comes the clinical psychologist. In the special schools, we are waiting with baited breath for those people to come," Rodriguez discloses.

The island's clinical psycho-logists are educated at the University of the West Indies, but the university only recently introduced post-graduate studies in the area. Not many of them remain on the island, however. Mrs. Rodriuguez believes they may be migrating because the salary is low.