By Toussaint Smith, Staff Reporter

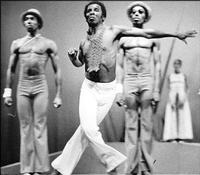

Prof. Rex Nettleford (centre) with Calvin McDonald and Michael Richardson, in the dance 'The King Must Die' (1968). - File

THE GLEANER has had its fingers on the pulse of the entertainment scene for decades. Naturally, our picture archives contain many a 1000-word story about those who have given us happy, memorable moments. In our new series, 'From the Archives', we pluck a pic and take a peek into the past, speaking to the central figure about the moment and subsequent events. Professor Rex Nettleford left on Tuesday for Curaçao in the southern Caribbean, where the sand is golden, the culture is unique and the nightlife is pulsating, with music like merengue, calypso, reggae, salsa, cha-cha-cha and other Afro-Caribbean rhythms. Curaçao sure bids him a warm welcome. The Sunday Gleaner had an opportunity to interview the man with many talents prior to his departure.

The story reads: The King Must Die, the NDTC's dance-work about political power, ambition and violence choreographed by Rex Nettleford. In the current season the role of the King is danced by Nettleford himself, who is here seen by Calvin McDonald and Michael Richardson, two of the 'revolutionaries-turned-goon squad-henchmen'.

Sunday Gleaner: Tell me about 'The King Must Die'.

Rex Nettleford: It has to do with power. The whole idea is that people create their leaders, but they crucify them too (chuckles) you know, with guarantee of resurrection or ascension. However, this thing which I did in the 60s remember now this was in the first decade of our independence I was a student of politics. I was very conscious of power and the whole thing of the adoration of leaders and how they suffer, so the King Must Die, you know. But a king must also live and the artist... what do you call it? The Queen Mother was very important in this and so in the belly, the Queen Mother is the one who pushes the son. He has his rivals the rivals come out of the very people who supported him who made him. In fact, the people turned on the rivals, first killed him and then turned on the young king and killed him too. The queen mother, of course, in the end throws away the symbols of power, the cape and the crown.

SG: What inspired the dance?

RN: The things that inspired me was thinking of Haiti, interestingly enough, and how Toussaint L'Ouverture was disgraced, taken away, put in exile and then Dessalines who succeeded him, was virtually chopped up, and this inspired me because Haiti as the first free state in the thing was an example we had to look at. Of course, American presidents were also assassinated, Lincoln... but that is not my concern, my concern is... it happened to all leaders... but the Haiti thing, in the belly itself you find certain symbolic-illusions; for example, the stool, the African stool which is a throne, it takes one back to Africa and the crown in a top-hat with a feather which many chiefs, paramount chiefs used to wear in Africa, all of those things, then the music was inspired by Africa beats and by Art Blakey. So the whole thing had a distinct rootedness in our history, our legacy and so on, and then, of course behind me are two gentlemen now my supporters. They become the Tonton Macoutes, the people who exercise power, the palace guards, the Tonton is wearing dark glasses there, so I used a lot of the imagery and what our people would understand. We revived it this year after taking it out of 'The Repertoire' and except possibly for one person, nobody else who was in the dance was born at that time, so it was created before people were even conceived, so this was quite an experience for them.

SG: Do you think the dance has the same impact now compared to then?

RN: Oh, the dance has tremendous impact! Definitely, but of course you don't throw away things, no more do you throw away record or a book, or you will read it again and in any case the theme is archetypal and it persists; even the political party rivalry that is going on right now speaks to that... and as it is always... it's so universal and it is timeless. So it's really a challenge and although we started out rather shaken in the season, by the end of the season it was really quite very good I think. I was satisfied with the two youngsters who took my part. It was a joy to stand at the back of the theatre and see them doing it, boy (laughs)... Kids who were not born when I was dancing.

SG: What do you think about the restaging?

RN: I think it went very well, and in fact, it was restaged by Barry Moncrieffe, who is my associate director, assisted by a young dancer/choreographer who was not even born at the time, but he looked at the video clips.

SG: How has your life changed since then?

RN: Well, since '68, the rest is history. I've done a lot of things, I've created a lot of works to begin with in the dance, have deepened my interests in culture and development. The dance to me is really a vehicle to demonstrate what can be done and, of course, my own progress in the university with different roles and my performance as Vice-Chancellor recently.

SG: What are you up to now?

RN: I feel that I'm I winding down, but I feel absolutely wound up but lots of people who are going into retirement, who have gone into retirement, your work is going to be more now than before, so I haven't stopped. I still teach, and I have a number of books to write and there is voluntary work I'm expected to do. I'm an ambassador-at-large and the whole thing of culture and chairman of the dance group/foundation, so I will have life to its full. I'm very interested in our people who live abroad, interested more in how they maintain contact and challenge us to let them have a sense of identity rather than simply how much money remittances they send back here. They have to show greater interest in that. My life in the whole thing of culture and it's centrality to development, because I believe in it strongly and I'm deeply committed to the idea of our identity. Here in academia, my interest is in cultural studies, naturally, because that's a thing that comes naturally from that. I'm also interested in ensuring that dance is not treated as the 'nevertismo' of the arts, but that of one of the central expressions of the creative imagination. And the response has been marvellous, you know, as one of the founders of the Jamaica School of Dance, now part of the Edna Manley College. I'm very pleased with the people we have produced and even the Company, we are finding a number of men who are going on to their Bachelors and Masters in Fine Arts, and they have been inspired by the company, and I'm very happy about that.